"You are not gonna believe where I am!"

I was there. I saw what Jake saw. I drowned in the fearful and delicate beauty of a too vivid dream and broke the surface gasping and grinning.

To do justice to the sights of Pandora and Avatar I should probably wait 15 years for my vocabulary to catch up. Visually, it is often mind-boggling. Stupefying in its lurid, psychedelic depth of colour, humbling in the magnitude of its detail, I gorged myself on the vertiginous battles that play amongst the boughs of great trees and beneath the waterfalls of floating Mountains.

Yet the true magic lies in the silence. A night-time trip through a luminescent landscape of glowing flora and fauna I am sure is one of the greatest sequences in all of cinema. It places the visual back where it should be: front and centre - I laughed, overflowing with the joy of discovery and the purity of new life.

Pandora gives Jake, a paraplegic, new life. He can walk again and he can run, curling his toes amongst the green reeds. All we see of his twin brother Tommy is his cold body, eyes closed, before he is slid into an incineration chamber. Later, Jake will lie down in a coffin-like capsule so that his mind may merge with his avatar host. "One life ends, another begins". Jake is Tommy's avatar. He gives new life to his brother too.

The first we see of Jake is his eyes bursting open wide. The film is not just about sight but insight; to look, to experience, yes, but also to understand and so finally to love:

"I see you".

We are told that humans have grown blind. They are selfish (Tommy was killed for the "paper in his wallet"). They have laid waste to their planet, taking until it can give no more. The army have come to extract valuable minerals from Pandora, to corrupt a new Eden.

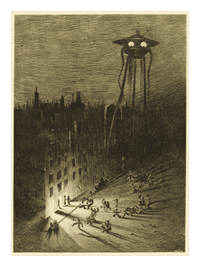

This time we are both the aliens and the humans of War of the Worlds. We are aliens crossing space seeking to survive through technologically advanced invasion and yet we are also the humans reproached for, in Wells' words, the "ruthless and utter destruction" that our "species has wrought".

Avatar is a fable that howls for peace with disarming clarity and earnestness. All living things on Pandora are linked like neurons in the brain. They are co-dependent. If you hurt one you hurt them all. The human race comes to Pandora in search of another mother, ignorant "like a child". While some repeat the same mistakes and take the path of destruction, violently sucking a surfeit of milk from her teat, Jake allows himself to be nurtured, cradled small in Neytiri's giant arms.

As a character Neytiri is captivating - fierce and loving, loyal and strong. As an artistic creation she is one of a kind. Neytiri is Snow White's great granddaughter. She too is drawn over and from a human performance. With Snow White it was rotoscoping while with Neytiri it is minute and intricate motion capture. All I can say is that I saw as much emotion on her computer generated face as on Sigourney Weaver's. The technology is able to discriminate too. We can see, for example, that Zoe Saldana's performance is more nuanced than Sam Worthington's.

The crunch of bone, the shattering of glass, the call of a bird, the plangent eyes of the Na'vi - the director wanted it to look and feel real. But now and again it feels more than that.

The crunch of bone, the shattering of glass, the call of a bird, the plangent eyes of the Na'vi - the director wanted it to look and feel real. But now and again it feels more than that.What prevents Avatar from being a masterpiece and one of the films of the year are two not insignificant qualms.

Firstly, for a film that shows us things that we have never seen before it is mired in what we have seen too much of.

A lonely man in a strange place, an untouched paradise, forbidden love and trials of strength; these are motifs that go further still into the past than Pocahontas.

At times the story, so time-worn, rings hollow, sparking no more than a Pavlovian reaction to the grand romance and earth-moving war. It is stirring but transient. I was left marking time. Furthermore, our hero faces challenges that are too easily overcome. His ultimate success and glory is never cast into any shadow of doubt. Jake's taming of the untameable Leonopterix is such a fait accompli as to unfold limply off screen.

Cameron's script is powerful and his direction spectacular and yet, frustratingly, he does, from time to time, fall upon the habits of recent blockbusters made by inferior film-makers: the blankly humorous one-liners that stand in for credible emotion ("let's dance", "outstanding") in Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight and the sweeping camera moves over insubstantial CGI hordes of Peter Jackson's the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

Secondly, for a film that is in so many ways so big-hearted it can also be mean-spirited and one-eyed. The soldiers and corporate bigwigs epitomised by Quaritch and Selfridge refer to the natives as 'savages'.

They are dismissed as inferior. They are not worth knowing. Yet it is these human invaders whom we do not get to know or understand. In the final analysis it is they who are treated and shown as savages.

They are dismissed as inferior. They are not worth knowing. Yet it is these human invaders whom we do not get to know or understand. In the final analysis it is they who are treated and shown as savages.They bawl their imperial catchphrases ("fight terror with terror", "win hearts and minds", "taking the money working for the company") but why are we not told of the desperation of life on Earth, the "dying planet"? What is unobtainium to be used for? In other words: what are they fighting for? I wanted to know.

Jake abandons his entire species (and his own human-ness) as if they can be only perpetrators and not victims, as if the sins we reap are only legacy and not inheritance. He boils human culture down to "light beer and blue jeans". Where is the compassion for all? "This is only sad", Neytiri says of a slain dog. If this is what they believe why do they consider that "the time of great sorrow was ending" if humanity is on its last legs? The Na'vi attitude is off-putting.

The fable is twisted. Innocence is lost.

An illuminating thought is that the only people who protect the Na'vi are the ones who have got to know them. Jake and Grace and Norm's morality is not absolute. They could have been just as cold and calculating had they not been given the opportunity to set foot in a Na'vi village. Happy are those who have not seen and yet believe exploitation and murder to be wrong. This is why I made the biggest connection with Trudy Chacon, played by Michelle Rodriguez. From afar she knew and sacrificed herself for the weak and unprotected.

Avatar is exhilarating. It is the stuff of tomorrow's nostalgia. I just wish that a film that often threatened to reshape the possibilities of Cinema hadn't ended up playing it safe. I wish that a film which could have told its tale with a smile hadn't sent its message with a scowl.

My ancillary writings on Avatar:

http://checkingonmysausages.blogspot.com/2009/12/avatar-american-flag-american-flag-in.html

http://checkingonmysausages.blogspot.com/2009/11/avatar-2009-and-fusion-of-male-and.html